Tools That We Use – Part 1 – Git

With this post we are kicking off a series of blog posts talking about the tools we use. The first one is about Git.

What is Git?

Git is a distributed version control system designed to handle everything from small to very large projects with speed and efficiency. But what is a distributed version control system?

Let’s break it down a bit. Firstly, Git is a content tracker mostly used to store code. A lot of times more than one developer is working on the same code. Additionally, changes to that code are made frequently. Git helps handling this by maintaining a history of changes to the source code. There are two places where the code is stored: remote repository (central server) and local repository (developers’ computer).

Before we dive into more technical details, let’s take a brief look into the history of git.

A short history of Git

The Linux kernel is the open source software project that is the main component of a Linux operating system. In 2002, the Linux kernel project started using a distributed version control system called BitKeeper. Before that, software changes circulated as archived files and patches. In 2005, the relationship between the company that developed BitKeeper, and the community that developed Linux kernel came to an end. As a result, the Linux development community, including the creator of Linux, Linus Torvalds, was prompted to develop their own versioning tool based on experience with BitKeeper. This is how Git was born.

Why do we need git and how do we use it?

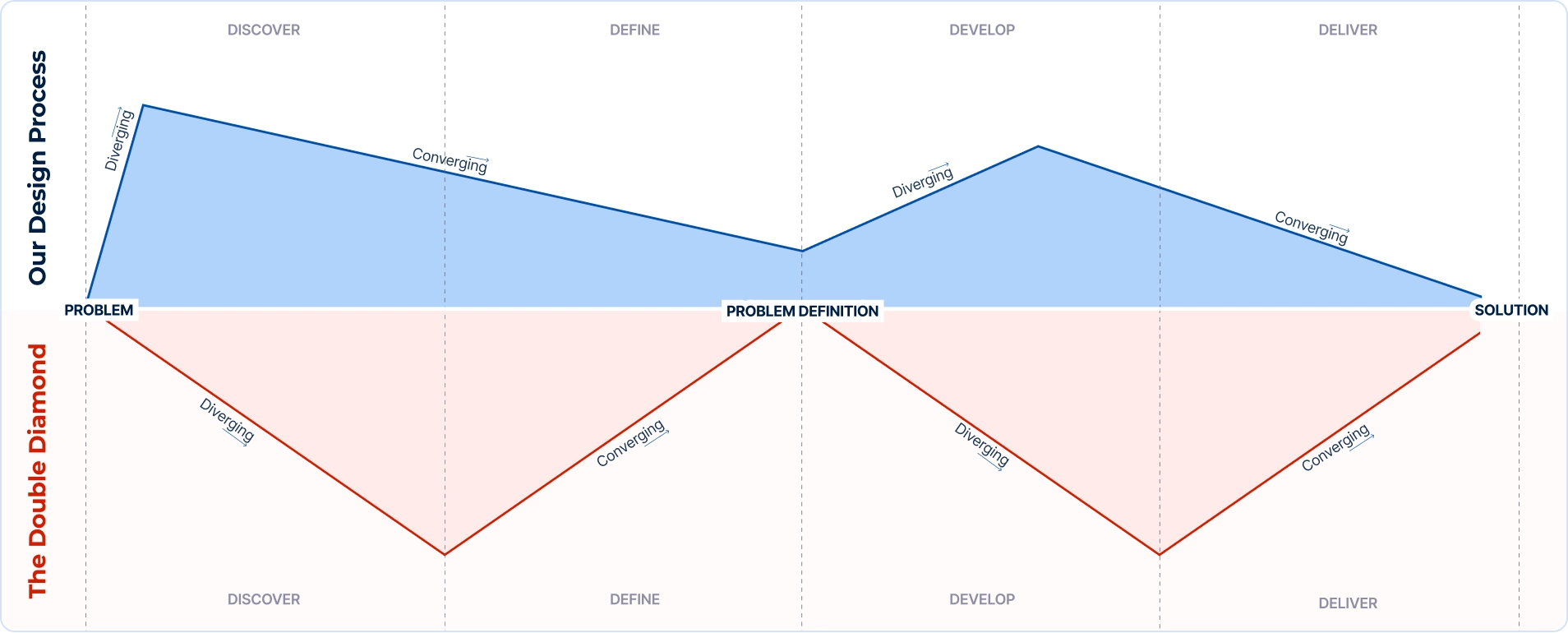

Projects frequently include multiple developers working on code in parallel. This kind of situation has a potential for code conflicts. Git often prevents conflicts with its basic usage and, when there are actual conflicts, helps resolve them in an orderly fashion . Moreover, requirements in projects often change, and, since Git keeps track of changes that were made, developers are able to go back to the older versions of the code. Git also has the possibility of ‘branching’ that allows flexible workflows such as: independent feature development, experimental code and even different projects with similar codebase.

Git is a tool that can be used either as a desktop application or as a command line interface (CLI). At Hexis, we use it as a CLI, because it gives us full control over the whole process of code versioning. The only negative aspect of this kind of usage is the learning curve, but once the developer gets accustomed to it, the CLI becomes the most powerful solution for managing git repositories.

Git workflow

In order to use Git more effectively and make your work more productive and consistent, it is advisable to stick to a certain workflow. Although there is no standardised way of interaction with git, members of the team working on the same project, should have an agreement on how the code changes are handled. Git workflows may vary based on company size, team preferences, type of project, etc. Since we’re using GitHub to host our repositories we’ll be writing from that viewpoint. The following git workflow may serve as an example for your next project:

- Fork

When you start working on a new project first you should create a copy of the main repository on your own profile. This action gives you a starting point for the project source that you will be making changes on. Why do we need this copy, why can’t we simply make changes in the main repository?

Sometimes you don’t have to write permission to work directly on the main repository (open source projects mostly use this model). Even if you have permissions we can easily fall into a trap of creating quite a lot of clutter in the main repository. Each user can then create branches, some of which may even be a valid part of the main repository but some are experimental and should be contained within a fork.

- Clone

Now that you have a copy of the project code that you will work on, in your own remote repository, the next step is copying this code to a local repository – your computer. This is where “git clone” comes in handy. It creates a copy of project code that developers can modify locally.

- Branch

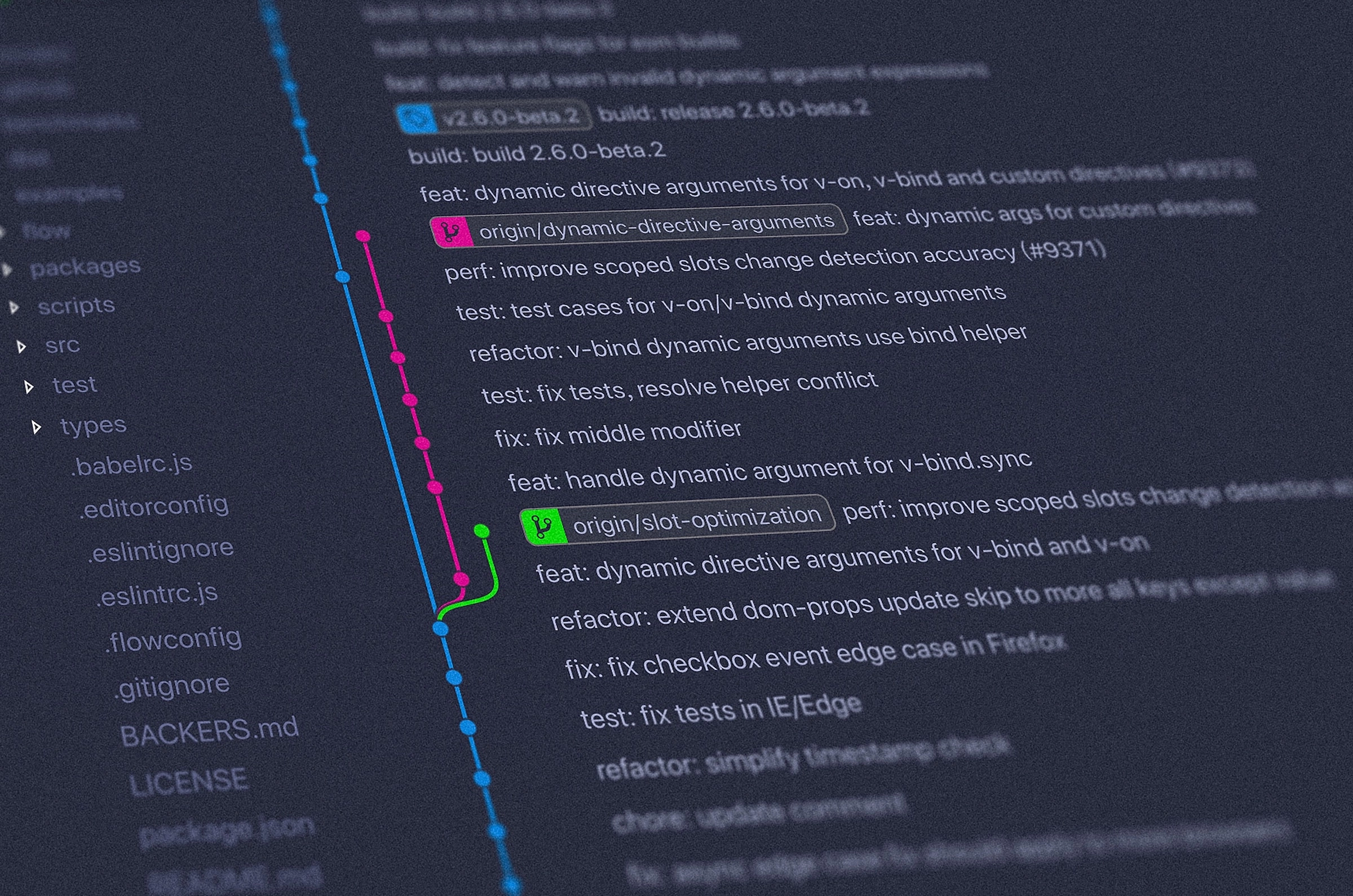

To make things neat and more manageable, developers have at their disposal something called a branch. Git branch represents an independent line of code development. It means that you diverge from the main line and work the code without messing with that main line. If you want to add a new feature or fix a bug, you create a new branch to encase your changes. Furthermore, branching makes it harder for unstable code to get merged into the main code base which can be really helpful. Branches can be created in both local and remote repositories. Usually we create a master branch that contains the most recent code ready for production.

- Commit

After we’ve made changes to the project code we need to save them in preparation for merge with the main remote repository. This “code save” is called a commit. Git command “commit” is used to snapshot the code changes in the local repository. A single git commit consists of: a unique identifier, code difference from the previous commit, timestamp and meta data about the author. Before you can save anything to your local repository you need to “git add” changed files to mark them for inclusion in a commit. Git commit captures the state of the project at that point in time.

- Push

After committing changes in your local repository, it is time to push those changes to the remote repository. Push transfers the data to a specified remote repository.

- Pull request

Before merging changes into the main repository developer that made changes to original code opens a pull request. Pull request tells other team members about changes that were made. Once it is opened, others can review changes, discuss potential improvements and finally merge the changes either to the master branch or any other.

- Merge

After the pull request is reviewed and approved it is time to merge changes into the main repository. Merging is Git’s way of integrating code changes that were made separately back into the source code repository.

A list of some git commands and their explanations

– git status: Shows us the current status of the local repository

– git pull: Takes the changes from an another repository and merges them into the current branch

– git checkout: A very powerful command that can, based on the parameters, discard changes on non-committed files, switch to another branch or even switch the state of a single file to a specific point in time marked with a commit hash.

– git rebase: Reapplies the current commit sequence, from the local repository, on top of the other commits. It gives a new base to the current commit sequence.

– git log: Shows us the history of commits along with some details like: hash id, author, commit message, etc.

Git hooks

A hook in our world is basically an action that happens at a certain point of script/program execution. We are in need of a hook when we have repetitive tasks. For example, if we find ourselves writing the ticket number in every commit on a project, we can automate it by using the hook named: prepare-commit-msg.

The previously mentioned hook is nothing but a script with this specific name, situated in a specific directory that executes a moment before the commit is made. Our command prepends the branch name to the commit message.

#!/bin/bash FILE=$1 MESSAGE=$(cat $FILE) BRANCH=[$(git rev-parse –symbolic-full-name –abbrev-ref HEAD)] echo “$BRANCH $MESSAGE” > $FILE

– post-commit: invoked after the commit is made. Usage example: triggering the “git log” command to see the commit details.

– pre-rebase: invoked before rebasing. Usage example: prevention from rebasing if the current branch is not the same as the branch we are rebasing from.

– pre-push: invoked before pushing. Usage example: prevention from pushing the code if any of the automated tests fail.

Git patches

Git patches are not used very often. In fact there are specific non-everyday situations where patches can be used.

The idea behind the patches is the avoidance of a central repository if for some reason we can’t or won’t connect to it, while still tracking the changes and being able to send them to someone for review. In fact, while using Drupal we can stumble upon a lot of git diff patches just by searching for improvements of their modules.

It works like this: the first user creates the patch file based on the changes in the local repository and sends it to another user, who will then apply those changes by applying the patch.

In conclusion, working on projects without some kind of code versioning would be devastating for everyone involved in it. There wouldn’t be any code reviews, time management would be extremely difficult to maintain, and in the end, the projects would be just a plain piece of code fallen from the sky with no development history.